I never got the chance to write the case for Pontus Holmberg before the Top 25 Under 25 started, but I’m taking it now, a little late in the game, because I’ve got a new tool to use to talk about this player and his chances of climbing up the rankings in the future.

The Player

Pontus Holmberg is, in many ways, Adam Brooks redux. He was drafted in 2018 in the sixth round, 156th overall, at the age of 19 after going undrafted the year before. Brooks went undrafted in 2014 and 2015 and was finally selected at age 20 in 2016 92nd overall. They’re approximately the same size, they both play at centre and wing, and the major difference is that Brooks put up huge points in his two final WHL seasons after being only mildly effective prior to that. Holmberg last looked like a major offensive force when he was still playing U16.

Of course Holmberg hasn’t been playing junior hockey all this time, the way Brooks did at his age, so that sort of comparison is pointless.

The Votes

Six of the voters ranked Holmberg between 20-25 on this year’s list, and that was fewer than had some of the others that just barely made the bottom of the list like Joey Duszak, which is why Holmberg came close to being ranked, but didn’t quite make it. I admit, I pushed him up in my rankings a little because I just really like him.

The Case For Holmberg

Holmberg had the usual sort of career a Swede who ends up drafted by an NHL team usually has. He was playing U16 hockey at 15, J18 (league play for U18 players) at 16, the highest level of J18 at 17, with an immediate promotion to the J20 team the next year. By the year he turned 19, he was well into a season with a full time roster spot on a men’s team in the division below Allsvenskan, after beginning the year with a very short stint in J20 again. He also had a two-game loan to an SHL team that year, just before the Leafs drafted him.

Any time you look at the stats of a player like this, you see seasons spent half on one team, half on the team up a level, with small batches of games in each place without any really exciting levels of points. Small samples can have wildly fluctuating results, and you never know what to take seriously.

His progression went: 1.84 points per game in U16, 1.32 PPG in J18 Elit, .51 PPG in J20 Super Elit, .56 PPG in Division 1 Men’s. This illustrates the problem faced by us when we rate a European: his points pace is almost guaranteed to go down not up, unlike a junior or NCAA player.

Long before the Leafs drafted Adam Brooks there was a very well-written article, that seems to have vanished from the internet, about drafting overagers. It made a very convincing case that Brooks was underrated. It raised a lot of very valid points about size bias, recency bias, and it concluded that looking at players in their second or third year of draft eligibility is valuable. Since that time, the Leafs have not shied away from drafting players in their second year of eligibility.

I never bought in on Adam Brooks, even if I agreed the concept had validity. I felt that too much of Brooks’ success was driven by a very high-event and high-offence WHL team, and he was comfortably situated behind Sam Steel in the lineup to make hay while the sun shone. Since then, Brooks has shown exactly what he’s good at: everything, but maybe not actually scoring his own goals all that much. Holmberg might be better at the everything, but he’s more challenged at the scoring part. Or at least, he seems to be playing in the SHL.

Holmberg’s post draft season

For those with an abiding fondness for points, they’ll see Holmberg scored three goals and had seven assists in 47 SHL games, and they’ll write him off. If that’s not enough, he was pointless in five games on Team Sweden at the WJC, but it bears asking, just how did he end up on Team Sweden if he’s so bad?

He wasn’t invited to the WJSS last summer. He was, however, tapped to play on the roster for a tuneup tournament that came after and usually features a B or C team. He was great. He ended up with five points in eight games, but he also caught the eye of the coaches because of his overall play. They put him in another set of games, and he successfully played his way right onto a WJC team that was weak at forward.

His play at the WJC itself was exemplary, and a couple of times he was the best forward on the team, and that’s why Sweden struggled. They had no offensive punch, and while Holmberg is a player who you see doing exactly the right things all the time, he never finishes. Ever, it seems.

That eye-test view held up over his season on Växjö in the SHL last year, where he was always in the lineup, but never the man getting the points. Why does he keep getting on the roster, then? Well, it turns out he’s pretty much a Corsi god.

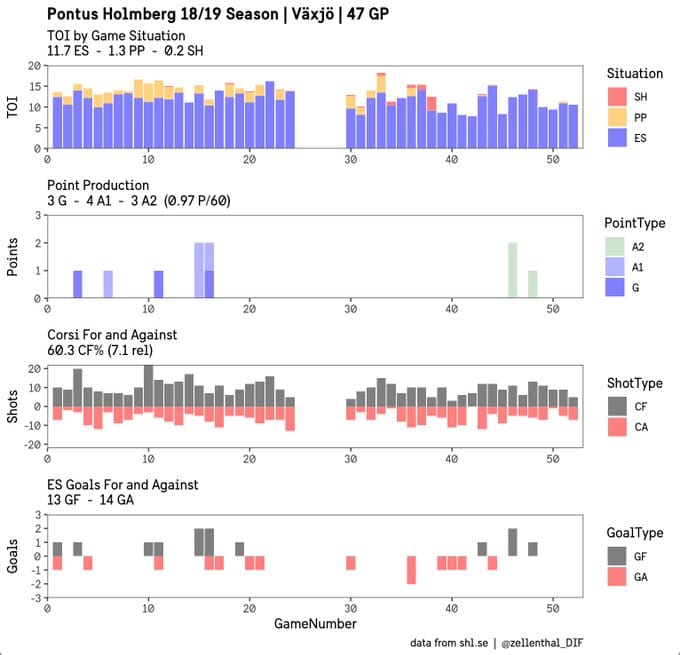

This is the work of Djurgården fan @zellenthal_DIF who has been compiling the newly available Corsi data from the SHL and creating these helpful visualizations. He confirmed for me that this is five-on-five Corsi data.

This chart shows game-by-game results, so beginning at the top, we can see the break for the WJC in Holmberg’s season, but there’s more to learn too. He began with some power play time, and then after he came back to the team, his overall ice time dropped, followed by a switch to some penalty kill usage from the power play and then to just five-on-five minutes.

In the early portion of the season, the coach was experimenting with a third line centred by Holmberg and usually featuring St. Louis first-round draft pick Dominik Bokk. When both Bokk and Holmberg returned to the team, Växjö was pushing for the playoffs and shortly after, they added (at great expense) Kris Versteeg. The youngest players all lost their ice time and special teams spots as the serious part of the season got going.

Notice, in the second row of the chart, that almost all of Holmberg’s primary points are clustered in the early part of the season. Skipping to the last row, the on-ice goals for and against, you can see that once Holmberg was playing fourth line minutes, the goals for disappeared, but eventually, so did the goals against. Once they got into it, he and the older veteran players he was on the ice with — Holmberg primarily at wing — were effective. Or lucky.

Now for the Corsi section. This is where we can learn a lot about Holmberg’s season beyond what just the raw numbers tell us. It’s really obvious that in the first section, Holmberg’s experience on the ice was a much higher-paced, offence-focused game than in the second part. The shots against are good, and the overall percentage is excellent, but the big driver of that percentage is a high CF. That all changes post-WJC. The pace of the shots overall drops, and while the shots against stay as good or better; the offence dries up quite a lot, but the overall percentage is still clearly positive. The result is a tale of two wildly different usages, both successful.

The raw number of 60% is impressive, but the very high rel number is more interesting. I haven’t delved deep enough into the Swedish Corsi results to know for sure, but in the Liiga, where there’s been Corsi for years, big percentages in the 60% or higher range for the top players is normal. You can’t use NHL expectations of parity for other leagues. The relative number of over seven tells you that Holmberg got the puck going the right way most of the time and it didn’t matter who he played with.

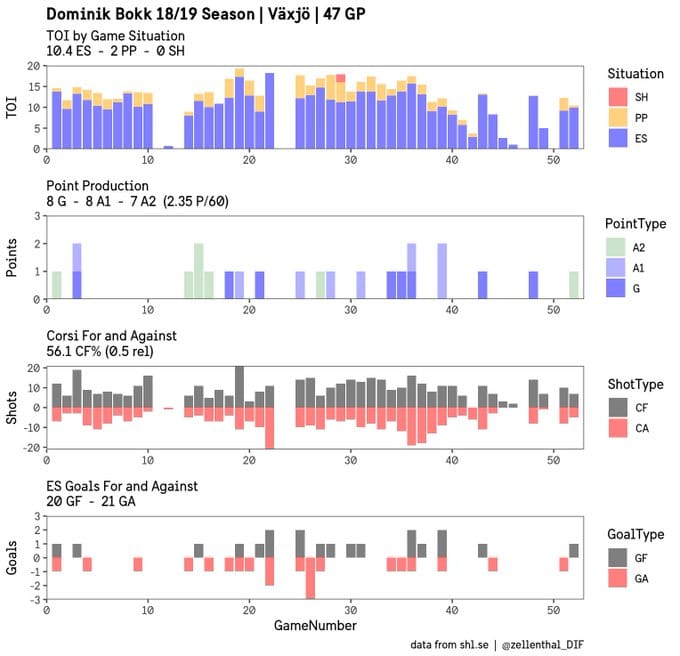

Now, let’s have a look at Bokk, the better young player with more offensive skills:

You can see the period at the end of the season where the coach didn’t always use Bokk, and you can see that even when he was in the game, he was sometimes the 13th forward. He gets points though, and he scores goals. But look at his Corsi, once Holmberg was busy off being a grinder. It’s, well, it’s pretty much what an offensively-focused, highly-skilled player produces in a league a little over his head when he’s 18 years old.

Conclusion

I am known to annoy fellow writers at PPP in the following way:

Innocent Hockey Fan: I just love that guy, he’s got such a great shot, sick hands, and he’s fast too.

Me: Yeah, but can he play hockey?

It’s really clear that Pontus Holmberg can play hockey. He’s good enough to genuinely hold down a roster spot in the SHL at 19. And he’s one of those guys, like Pierre Engvall, who the coach loves. And gets frustrated by when he never scores.

Before Zach Hyman became a member of the Leafs, he played at the University of Michigan and really didn’t impress anyone. Then suddenly he had a great season, he led the team in points, and a superficial observer might have thought he was a top-six scorer in the making. A quick look shows he got those points by playing with Dylan Larkin, Andrew Copp, Tyler Motte, Zach Werenski and J.T. Compher, and that is a lot of future NHLers for one NCAA team. It was reasonable for Leafs fans to not think that much of Hyman at that point if they realized how stacked that team was.

Once Hyman got on the Marlies, and ground out 37 points in 59 games playing on a team with T.J. Brennan, Mark Arcobello, Brendan Leipsic and Josh Leivo — a lot of NHL/AHL tweeners of high quality, oh, and William Nylander — his true nature was revealed. He wasn’t leading that team in points, but he sure could play hockey, though.

Once he got on the Leafs, his status as a Corsi god who never scores was cemented. He’s not a universally popular support player on the Leafs. Many fans who demand sick hands at all times find his work-ethic, always-on, hard-grind, “here’s the puck, guys” game hard to find value in. Of course, his coaches love him.

So Holmberg, then, where is he on the Brooks to Hyman continuum? Somewhere in the middle right now, and it’s going to be very interesting to see how high he can take his skillset that only a coach can love.

Comment Markdown

Inline Styles

Bold: **Text**

Italics: *Text*

Both: ***Text***

Strikethrough: ~~Text~~

Code: `Text` used as sarcasm font at PPP

Spoiler: !!Text!!