In a recent 32 Thoughts, Elliotte Friedman quoted Bill Daly about expansion. One of his remarks caught my eye, emphasis mine:

20. He anticipated one question before I asked it: Does the talent level exist to support more teams? “The quality of the talent on the players’ side is better that it's ever been and deeper than it's ever been. I don’t worry in terms of dilution of talent. Skill level is off charts, the league becoming younger and younger. … Not concerned about it.”

Bil Daly is far from the only person to say this with confidence in the last few years, but he is someone who could have that verified with an inter-department email and a wait of about 15 minutes. Even most journalists could use their access to paid portals to NHL stats to find out if this thing they disclaim in short, firmly stated declaratives is true at all.

I was skeptical, not just because all generalizations about demographics in hockey usually end up to be what a person wants to believe, not what they actually have any evidence of. I was skeptical because there are forces exerting pressure on NHL GMs that push against any desire to play younger players more than they used to. Some of these are recent flat-cap issues, some are the way the CBA works and some are about bigger changes in the NHL than expansion.

My impressions of the league aren't reliable, though, because when you watch a team going through a rebuild and then experiencing natural growth towards more experienced and older players, you can start thinking either that the Leafs are doomed, doomed I say, because they aren't getting younger and younger, or you can think the entire NHL is like the Leafs. So I need to verify this with some actual facts, but first what I see as the systemic issues that keep the NHL ticking along with middle-aged players taking most of the jobs:

- The most obvious thing here is the ELC rules. At first blush, it seems the ELC restrictions keep salaries artificially low and should encourage cap-conscious teams to play more young players. But are they low? Some sure are. Even with max bonuses, Auston Matthews or Connor McDavid were bargains on their ELCs. But most people might actually be overpaid. The lowest ELC cap hit last season was $855,000, but there were 440 players on standard contracts with an AAV less than that. Some of those are RFA age, but a lot of them are older. Take the ELC rule, add a flat cap and you have pressure to leave the youngest depth players in the AHL while you find an older player to take league minimum.

- Take point one and add the emergency exception threshold (league minimum plus $100,000), something that got expanded in use during the Covid seasons, and you've got even more pressure to keep the younger players from getting in games and very good reasons for older borderline players to take less money to get playing time.

- The less obvious thing is that the NHL, like all the rest of the athletic world, has figured out how to make humans perform better and to maintain their physical condition over time. That could well lead to an increase in older players or an increase in the extent of the peak performance years.

- The most obvious issue is that, particularly for the cheaper depth players, coaches and GMs want known quantities. And that means older.

That's all guesswork, but it's why I expected the NHL to not have got any younger in the recent past, and to not be trending that way now. But what exactly do people mean when they say "getting younger". Daly clearly is saying that during the period of recent expansion, the NHL has become younger, and he's implying that is ongoing.

Off to NHL.com I go and carefully copy out by hand all 10,000 plus player bios for every skater on an NHL team since 2012. Goalies are too weird for this sort of endeavour. I picked 2012, the year of the lockout, because that period marked a change in the CBA, and covers a period of inflation in the salary cap and then stagnation during Covid. It's 12 years, and that's long enough to see if there is an ongoing trend.

The bluntest method is just to take the mean age for each season from the entire dataset.

| Season | Mean Age |

|---|---|

| 2012-2013 | 26.72 |

| 2013-2014 | 26.57 |

| 2014-2015 | 26.48 |

| 2015-2016 | 26.22 |

| 2016-2017 | 26.02 |

| 2017-2018 | 26.05 |

| 2018-2019 | 25.98 |

| 2019-2020 | 26.14 |

| 2020-2021 | 26.23 |

| 2021-2022 | 26.32 |

| 2022-2023 | 26.56 |

| 2023-2024 | 26.79 |

I could just quit now because the full set of players includes all those guys who played a few games in October and then got sent back to junior or the AHL so this is likely the lowest number I can get. As the cap got flat, the mean age went up after a similarly gentle decline in the prior few years.

But I don't want to know who has one game played in a given season. I want the people who really played, so I cut the dataset off to only those players who had at least half a season in games played.

| Season | Mean Age |

|---|---|

| 2012-2013 | 27.36 |

| 2013-2014 | 27.36 |

| 2014-2015 | 27.35 |

| 2015-2016 | 27.11 |

| 2016-2017 | 26.95 |

| 2017-2018 | 26.65 |

| 2018-2019 | 26.62 |

| 2019-2020 | 26.85 |

| 2020-2021 | 26.93 |

| 2021-2022 | 27.22 |

| 2022-2023 | 27.53 |

| 2023-2024 | 27.72 |

The actual players who are regularly rostered players are older, and have been getting older lately.

When population age is studied, usually to give governments information about how older people cost more in social programs so they can ignore totally the coming demographic crisis, a technique is used to show the percentage of each year's population that are over a certain age. This can give a more fine-grained answer than just a mean. So I decided that I would use age 26 as the proxy for UFA age – which is decently close. So using the set of players that played over half a season, what percentage are under 26 on July 1 of the year the given season starts.

| Season | % < 26 |

|---|---|

| 2012-2013 | 41.61 |

| 2013-2014 | 42.63 |

| 2014-2015 | 42.16 |

| 2015-2016 | 46.30 |

| 2016-2017 | 47.54 |

| 2017-2018 | 50.34 |

| 2018-2019 | 48.46 |

| 2019-2020 | 45.49 |

| 2020-2021 | 45.49 |

| 2021-2022 | 42.22 |

| 2022-2023 | 38.54 |

| 2023-2024 | 35.31 |

By this measure the proportion of younger players was lower last year than back in 2012-2013, showing that not only is the NHL not getting younger, the mean age hides how very not true this has been lately.

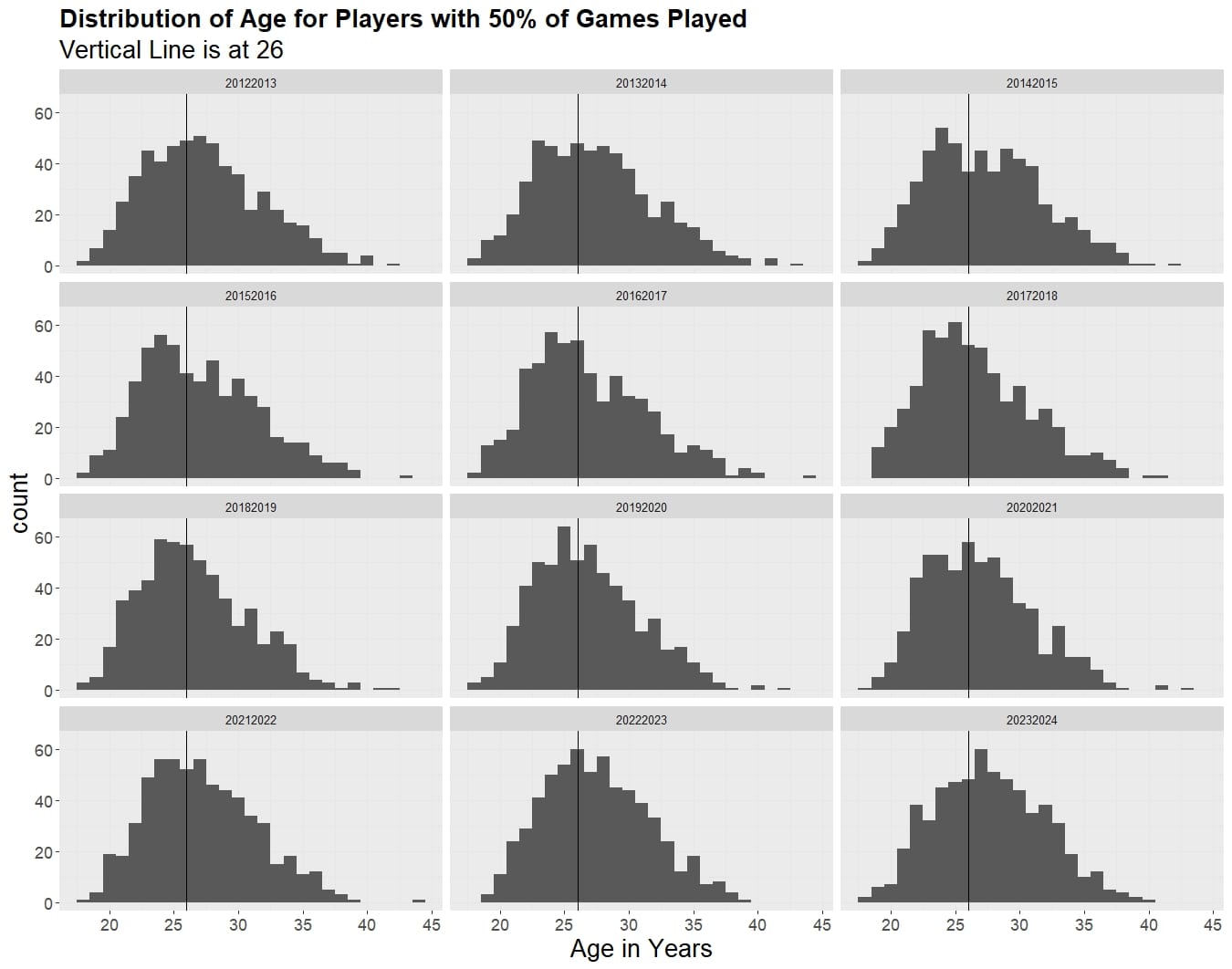

And I'm here with all these numbers, so how about the distributions for each season?

This made me actually want to have an old-age percentage on the group as well because it's hard to see the changes on the right tail.

| Season | % 35+ |

|---|---|

| 2012-2013 | 6.47 |

| 2013-2014 | 5.44 |

| 2014-2015 | 6.10 |

| 2015-2016 | 5.46 |

| 2016-2017 | 6.16 |

| 2017-2018 | 4.58 |

| 2018-2019 | 2.74 |

| 2019-2020 | 3.07 |

| 2020-2021 | 3.58 |

| 2021-2022 | 4.14 |

| 2022-2023 | 4.55 |

| 2023-2024 | 5.12 |

It isn't the very oldest players going up that's driving the older NHL all that much, it's the middle aged. Will the rising cap change that? It might, but no matter how much people might want players to play when they're 22 years old, coaches and GMs aren't on board unless they are sure they have a reliable player who adds value.

To turn the saying about height to a new use: Players over 25 have to prove they can't play, players under 26 have to prove they can.

Next time you hear the younger NHL line, you'll know it's not true. Funny how the NHL giving PR time to a few young stars seems to correlate with the proliferation of this opinion, though.

Comment Markdown

Inline Styles

Bold: **Text**

Italics: *Text*

Both: ***Text***

Strikethrough: ~~Text~~

Code: `Text` used as sarcasm font at PPP

Spoiler: !!Text!!