We've been at this for a while now, this version of the Leafs where they actually try to be a good team. Every summer, they add to the core of stars, trying to make a whole team that can compete, and the result has been a playoff team for eight years. In all those years the first thing that happens every offseason is fantasy trades or wishcasting signings of high-end forwards.

It's funny on the one hand, but very understandable. Forwards are just easier to understand, and they're more fun. I just read through the PWHL draft eligibility list, and I know who the wow-factor forwards are, but I'm going to have to do a lot of research on the defenders.

Measuring Defence

Is the past really prologue?

In the 1950s, the NHL was small like the PWHL, and the people trying to gain a competitive advantage for their teams could realistically scout every player in the league and in the minors. But even then the desire to understand the way in which defence and offence balanced out in players was strong. When the question was who was better defensively, the answer was an opinion. What the people involved in hockey wanted then was a solid answer. Hard, cold numbers.

They invented plus/minus. We all know now that plus/minus lies too much to have value. That even if you understand the way it makes a PK defender look terrible when he might be your most necessary player, you still can't mentally adjust the numbers to tell you who is good and who isn't.

Goals For percentage is just plus/minus in a fancy suit and a snappy pair of designer black-framed glasses. There's too much else in there – the goalies, the other skaters, randomness, usage, the overall team quality, randomness, and a million other things. It lies too much.

We look at shot-based measures like Corsi and Expected Goals , which lie a little less, and then we shave off some of the lies with models to isolate individual impacts, but it's still lying to us. The past can't predict the future with perfection. Sometimes it does nothing but describe what did happen and can't give you even a clue about what will.

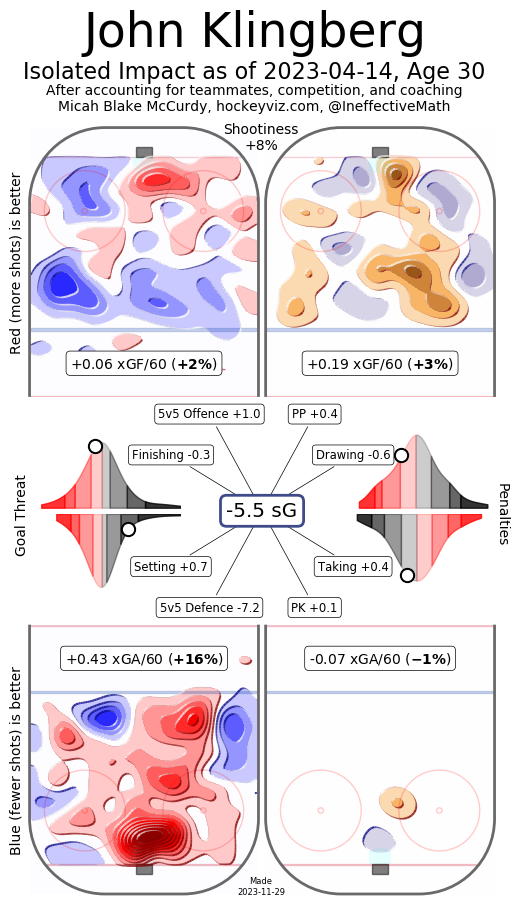

A reasonable person could look at this and not sign the player:

That information can't be relied upon to tell how that the next season he would actually degrade offensively even as a better team buoyed up his defence by a small and not very helpful amount.

I think you have to scout heavily to really find the defenders you need. You can pretty much buy a forward off of Amazon, maybe read the reviews, check the star rating, and you'll do okay. Defenders? You have to see them. But what are you looking for?

Roles and role reversals

This is player evaluation season. We're going to be talking about draft prospects a lot starting next week. We're going to keep fantasy trading for forwards, and every defenceman who has ever had positive attention (for points) is going to be held up as the answer to all the Leafs' problems. I'm ahead of the game on this thinking about how to pick a defender. Brigs has written a lot of draft prospect articles, I've read them all, and a lot of them are about defenders and how you evaluate defence.

Somewhere over the last few years, he and I have independently come to a fairly similar and revised understanding of defence in the NHL. We had never talked about it a lot, but he's been mostly looking at draft prospects, I've never looked at junior hockey until this year with the London Knights, and we met in the middle with a reworking of old ideas. Top defenders in the draft are big points producers, but lack of points can hide some excellent defenders from attention, and size does matter for defence. Now, the truth is, size has always mattered for every hockey player.

Let me talk about some easier to understand forwards who each exemplify a "type". These two forwards play on the same team, play on the same line sometimes, and one is seven inches and 13 pounds larger than the other. They are both top-level players, up for awards they richly deserve. But they don't play the game the same way. The shorter one is a pest, causing trouble and driving the net, getting into scrums along the boards. The taller one is a pure scorer who is also built like that proverbial structure made of brick.

These two players are Emma Maltais and Natalie Spooner. And the brickhouse that is Spooner drives up the ice and gets into scoring position in a way very much like Nate MacKinnon (nicknamed Moose in junior hockey). MacKinnon is only six feet, two inches taller than Spooner, and he isn't really known as a big player. He is a powerful player though, partly because he's a powerful skater like Spooner.

Maltais is powerful in her own way, and she will make you think of the small but bulky players who "play big". But she hasn't got much reach. She needs some speed to compensate, some agility, and she isn't going to be a wizard defensively with her stick.

Size isn't just extreme height. Joel Edmundson at 6'5" and 225 lbs uses his size, his power and his reach – and the very long stick that every very tall player uses – to his advantage. But those traits don't make him a top-pair addition at the deadline.

At the other end of the spectrum, Timothy Liljegren's lack of physical power is a weakness other teams can and do easily exploit, and they do that primarily when he is trying to defend at the net-front. I don't believe in Topi Niemelä as a potential NHL defender for this exact reason. With both of these players, they haven't got the reach from above average height, and they haven't got the heft of above average weight. The players of that size that succeed are very highly skilled: Quinn Hughes, John Marino, Adam Fox, TJ Brodie. Most of the smaller defenders in the NHL are not defensive specialists who PK like Brodie. It's unusual for a player to not need the reach and weight advantages.

It's understandable for so many reasons that fans who understood objective measures of player value got very tired of big, impressive looking defenders, and started demanding that teams get players who did more than look the part. Liljegren has a lot of fans who want him to succeed more than he has done because of what he represents. He is the "modern, puck-moving defenceman" and "size doesn't matter" all in one package, but slogans don't win hockey games, and I believe that it is equally and exactly as wrong to want this type of defender for his symbolism as it is an Edmundson type.

We have to get off this reductive polarization of player skillsets – which is just another edition of the skill/grit false dichotomy and look for a defender who can succeed on the Leafs. Power, reach, agility, skating, smarts, all of these things combine in a player, and we should stop valorizing the skills that get lumped into the word physicality either for their own sake or for the sake of their absence.

What is a defender, anyway?

The answer to this question is not as obvious as it seems. I think our haziness on understanding defenders starts with the way we think about them in relation to forwards. We tend to think of defenders as forwards in reverse. Their primary role – with a few very famous exceptions – is to prevent goals being scored, just like forwards are there to score them. I think this leads us astray and not just from oversimplifying things.

A defender is not an inverted forward. Let me show you with Goals Above Replacement. GAR is a mildly annoying (to me) system of measuring player results that bakes in all the goal-scoring randomness, but shows you what that player made and had happen to them using net goals for and against as the unit of measure. It measures luck and skill all mixed up and tells you fairly accurately what the player's share in the results were, while not really telling you who they are at their core.

Evolving Hockey's GAR skaters, with at least 300 minutes of even-strength TOI returns 682 players, or every seriously used NHLer this season. GAR is split into offensive and defensive. The top offensive GAR player is Nate MacKinnon with 29.6. The top defensive GAR player is Alex Vlasic (whom I love) with 10.4. You need three defenders on the ice to counter MacKinnon and they all have to be having the season of their lives.

The inverse of a star forward is not a star defenceman, it's a star goalie. The goalie is tasked with preventing goals as a primary function, not the defender. The defender does other things, and it's not always true that the defender's primary job is to limit shots against, but that's a good place to start.

The defender helps to limit shots against in volume and quality. We can measure that with Corsi or Fenwick Against and Expected Goals Against. We can use models like HockeViz or Evolving Hockey's RAPM to identify the player's personal impact on those things.

Next, the defender facilitates zone exits. That's going to show up in the numbers we just looked at, but there are some tracked data (I don't mean the NHL's it's not public) that can identify particular skills.

Next the defender facilitates moving the puck through the neutral zone, over the offensive blue line, and into the offensive zone, and he helps to keep it there. HockeyViz has some information about player impacts on the puck travelling over the blue line.

The results of all of those things the defender does shows up in shot-based measurements. His impact on offensive shots and Expected Goals For can also be seen. Everything the defender does, from stick checks to body checks to falling down to skating fast or getting beat on the backcheck shows up in the big-picture shot-based measures.

This form of measuring can feel like finding planets in space by looking at the gravitational forces on the other bodies we can see. It feels indirect, and frustratingly undetailed. It goes wrong sometimes too. Coaches get their fingers into things, and the underlying assumptions of models – that all players play on teams that actually try to win games all the time don't actually hold true.

This is why, for NHL teams, they have to scout. And they have to have scouts smart enough to forget about points and how much a player just looks like their stereotype a defender to find the players who really do the job. What job exactly, though?

Leafs history

HockeyViz has this neat graphic showing the defence pairs for a team, this is this year's:

You can go tab through the seasons if you like, back to 2016-2017. But it neatly eliminates the noise around third-pairing guys and focuses your attention on who actually played meaningful minutes.

Back in Auston Matthews' first season with the unexpected trip to the playoffs, the top four were: Rielly - Zaitsev - Gardiner - Hunwick.

The campaign to improve that better became a yearly event:

- 17-18: Gardiner - Zaitsev - Hainsey - Rielly (all within an average of one minute of each other so ignore the order)

- 18-19: Rielly - Gardiner/Muzzin - Zaitsev - Hainsey (Gardiner and Muzzin only overlapped for about 15 games)

- 19-20: Rielly - Barrie - Muzzin - Ceci/Holl (Holl ended up as a de facto alternate number 4 due to injuries to Ceci and Muzzin)

- 20-21: Rielly - Muzzin - Brodie - Holl

- 21-22: Rielly - Brodie - Muzzin/Giordano - Holl

- 22-23: Rielly - Brodie - Holl - Giordano/McCabe (McCabe took Giordano's spot, and he took Sandin's)

You know, there isn't a single year I wouldn't take over this year. If you set out to have a unsuccessful set of four defenders in multiple combinations, you couldn't do better without trading Morgan Rielly first. A lot of the trouble was Brodie's sudden lack of success, but that wasn't the whole problem.

The other obvious thing if you look at all the charts of minutes, is that both Sheldon Keefe and Mike Babcock have been playing their defenders as if the top four/bottom pair split actually makes sense. It does not. In most of those groups the middle pairing should play about 3-5 minutes less and those minutes should be split with the top pair and the third pair. The surplus on the bottom, and the weakness on top led Keefe nearly to that system this year.

Getting over the past

TJ Brodie is not going to be re-signed, I think that's clear, so the Leafs have this arrangement:

Morgan Rielly - ???

Jake McCabe - ???

Simon Benoit - ???

I don't believe the Leafs will keep Timothy Liljegren, and I'm going to go on assuming that is the case. The other defenders under contract are Conor Timmins, Cade Webber and a host of other AHLers. None of those players are answers to the question marks beyond possibly doing some third pair minutes as recall options when whoever is actually signed to do that job is not available.

I'd just sign Joel Edmundson if he was interested, and stop thinking about anything outside the top two needs

Now, finally, it's time to define those two needs. What skills do they need, what expectations should the team have of who they get. What roles are open?

Every team needs two legitimate power play defenders and one guy who can do it well enough to not make you cry. The Leafs have one elite power play man in Rielly and the no-cry role covered with McCabe. They need one of their new acquisitions to be better than McCabe. This is actually one of the problems with Liljegren, even if you believe (I don't) he is a fit for the open spot with McCabe, he isn't a value-add on the power play at all, and has been a spectacular detriment in some years.

If you look at the historical record you see two intensely unsuccessful attempts to replace Rielly on the top power play unit. This is a foolish misuse of scarce resources. The Leafs can have the best power play in the NHL with the players they are likely to have on the team this coming season. Save the cap space and assets and just get a second unit guy.

The Leafs need four defenders who can play the PK decently well. That's not Rielly, and he should only be out there like Matthews is in the last 20 seconds getting ready to rapidly transition to offence. McCabe is okay, so is Benoit, and it's clear two more are required. Your regular third pair right-shooting defender can be tall with a big reach and enough skill to be a regular there. Edmundson, in other words.

It feels very much like one of the two new players might need to be a bit of a jack of all trades defender who is better than McCabe on the power play, at least playable on the PK, and tilted enough to defence at five-on-five. These players are hard to find because fans hate them. They have weaknesses, or are just less than elite across the board like McCabe, but good in the aggregate.

The expensive one had better be the hottest defensive defender money can buy. Jake Muzzin redux. A player with puck skills and net-front skills, power and smarts. These players are hard to find because most teams don't want to give them up.

This shopping list means one thing: stop looking at points. We're not looking for offence as a primary attribute. At the same time, I don't think the Leafs want another Benoit, who has defensive value only. So we might want to look at how the potential defenders add to offensive value, but not in terms of personal shooting or heavy involvement in offensive cycles.

This really needs a professional crew of scouts, but that's not going to stop us from looking at who is out there and fantasy trading/signing for someone a lot less exciting than whatever winger you like this offseason.

Coming soon: a look at the list of defenders who could be plausibly available.

Comment Markdown

Inline Styles

Bold: **Text**

Italics: *Text*

Both: ***Text***

Strikethrough: ~~Text~~

Code: `Text` used as sarcasm font at PPP

Spoiler: !!Text!!